No assembly required. Just puff. That is about all you need to make a soap bubble. Well, of course you need soapy water and something to make a thin layer of soapy water. But add a slow and careful puff of air and you’ve got everything you need to make a beautiful bubble.

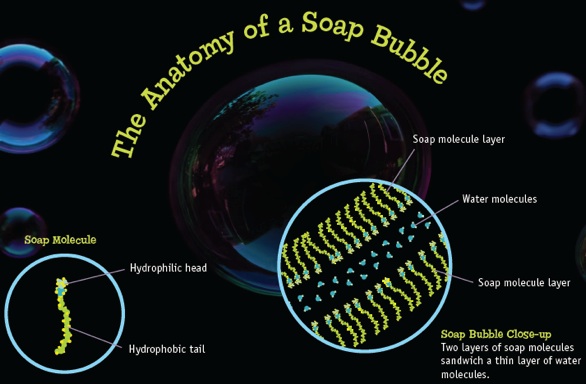

You don’t have to build the bubble bit by bit with your hands. When you blow a bubble, the soap and water molecules organize themselves automatically into thin layers through the process of self-assembly. Soap bubbles are made of a layer of soap molecules, and then another layer of soap molecules all kind of sandwiched together (think a piece of bread, a piece of cheese, and another piece of bread). Except that this sandwich is really thin, about 1/100th the width of a hair. The layers are so thin that you can’t see them with your eyes.

So why does a puff of air cause these thin layers to self-assemble? How do the molecules know which way to move? And why do they make a big bubble instead of just flying off into the air? Well, soap molecules have two different parts—one part likes water and the other part doesn’t. The part that likes water is called hydrophilic, the part that doesn’t is called hydrophobic (hydro=water, phobic=afraid of). When there’s a little water around, the soap molecules form a layer with the part that likes water on one side of the layer and the part that doesn’t like water on the other side. Do that on both sides of a thin layer of water and, presto, you have a bubble.

There is another nanoscale phenomenon that happens with soap bubbles. Look closely at the bubble and what do you see? Colors—all of the colors of the rainbow. And what’s cool is that the colors change as the bubble is carried along by the breeze. At the nanometer scale, unexpected things happen, including the bending of light. The thin layers in a soap bubble diffract light and, depending upon the thickness of the layer, different colors of light are diffracted. So the surface of a soap bubble looks like lots of little swirling rainbows because the thickness of the layers is always changing. The layers don’t change much, only a few hundred nanometers, or less than one-thousandth the width of a hair.