Not everything that is made on the nanometer scale is made in a laboratory. Nature is full of nanometer-sized stuff, some of which happens by self-assembly. DNA and proteins are made using enzymes, little tools that take the parts and put them together, so these are not self-assembled. Then what is?

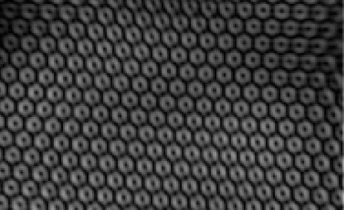

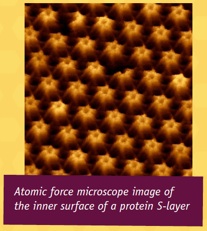

Well, on the outside of some bacteria is a material called an S-layer. S-layer stands for “surface layer,” which proves that scientists are not always clever in figuring out names for things. An S-layer is made up of just one protein that has the special ability to form large crystals (sort of like salt). The crystals are two-dimensional, flat, and made up of only a single layer of protein.

What’s cool about the S-layer is that it has tiny holes only a few nanometers wide, spaced out a few nanometers apart. Think about a window screen, the kind that you use to keep out bugs when the window is open. But the holes on an S-layer screen are about a million times smaller. That is so small that even most molecules can’t fit through.

Why do bacteria need S-layers? S-layers help give bacteria shape. Without them many bacteria would just be a big blob and shape is sometimes important. S-layers also might protect the bacteria from other things, like other bacteria. But S-layers probably also help keep most molecules inside the cell and other molecules outside of the cell. Kind of like a barrier that separates the inside of the cell from the outside.

Are S-layers useful to us? Scientists are very interested in making nanometer-scale structures. They are using S-layers to make nanowires, really thin wires that are a lot taller than they are thick. How thick? A few nanometers, and thousands of these will fit across the width of a hair.

One thing that nanowires can be used for is making rechargeable batteries. Scientists think that nanowires would make really good parts for batteries—batteries that last longer and hold more of a charge. All this from a little bacteria… all this stuff that is made by self-assembly.